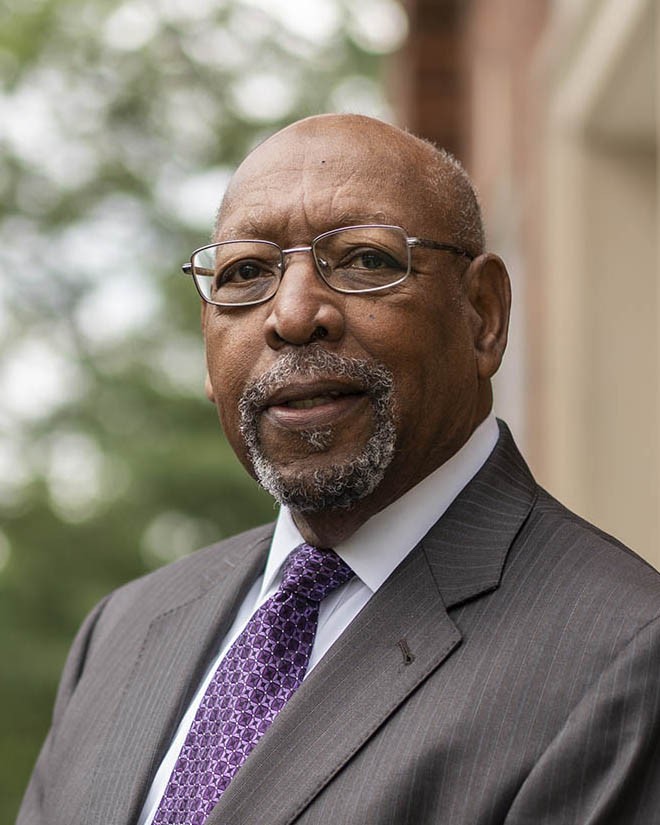

Dr. Richard Green, c. 1961 (1940 - Present)

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Richard Green attended Concordia College during the tumult and excitement of the early modern Civil Rights Movement, becoming the college’s first African American graduate in 1961. A chemistry major, Green went on to earn a master’s degree in science at North Dakota State University (1963) and his PhD in the field of inorganic chemistry at the University of Louisville (1969). In 1964, Green married Dorothy Reed and began work at a chemical firm in Louisville. Richard and Dr. Dorothy Green have two adult children, Richard Clayton and Kim Elizabeth and three grandchildren. Richard C. is a graduate of Stanford University and Kim a graduate of Northwestern University. Green returned to Concordia in 1969 as an assistant professor in the department of chemistry. He became the first director of the college’s new Office of Intercultural Affairs in 1971, helping to make Concordia a more welcoming place as Black and Native student enrollments increased under his leadership. Green served on the Board of Regents from 1972 to 1981 and aided Concordia College by acting as a mediator during the Black Student Strike of 1976. Green’s career followed numerous industry, faculty, administrative, and academic leadership posts across the nation, earning him the highest esteem as a respected and sought-out leader in higher education.

A native of Louisville, Kentucky, Richard Green attended Concordia College during the tumult and excitement of the early modern Civil Rights Movement, becoming the college’s first African American graduate in 1961. A chemistry major, Green went on to earn a master’s degree in science at North Dakota State University (1963) and his PhD in the field of inorganic chemistry at the University of Louisville (1969). In 1964, Green married Dorothy Reed and began work at a chemical firm in Louisville. Richard and Dr. Dorothy Green have two adult children, Richard Clayton and Kim Elizabeth and three grandchildren. Richard C. is a graduate of Stanford University and Kim a graduate of Northwestern University. Green returned to Concordia in 1969 as an assistant professor in the department of chemistry. He became the first director of the college’s new Office of Intercultural Affairs in 1971, helping to make Concordia a more welcoming place as Black and Native student enrollments increased under his leadership. Green served on the Board of Regents from 1972 to 1981 and aided Concordia College by acting as a mediator during the Black Student Strike of 1976. Green’s career followed numerous industry, faculty, administrative, and academic leadership posts across the nation, earning him the highest esteem as a respected and sought-out leader in higher education.

Richard Green first came to Concordia College in the fall of 1957 after being recruited from a segregated public school in Louisville, Kentucky. Moved by events surrounding the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Concordia’s Student Association hatched a scholarship campaign designated for a Black student from the South that supported Green’s attendance. Green himself expressed interest in Concordia for the adventure of a new place and a different culture. Green stated, “I had never had a white teacher and classmates or a white administrator.” With encouragement from his school counselor, Green decided to attend Concordia. He boarded a train for Moorhead. Arriving alone, Green hired a taxi that took him to Brown Hall. “I began to wonder where I landed,” he recalled. [1]

Green would become an active student. In addition to study of chemistry and mathematics, Green especially enjoyed taking philosophy classes. Beyond the classroom, he participated in basketball, tennis, student government, worked the sound system for chapel, and joined Chi Delta Phi. Green recalled a time when he had to get a haircut. Though apprehensive, he simply went to a barber shop in town, sat down, and the barber cut his hair without question. Rarely did Green experience overt discrimination. However, on one occasion a hotel would not allow the tennis team to stay if it meant that Green would be staying in one of the rooms, an event that Green discovered only later as a faculty member at the college. Green was grateful for those students and faculty who welcomed him at the college. Like many college students, he spent breaks with the families of his friends. J. L. Rendall, a Concordia administrator, and his family were particularly welcoming to Green. Green remembered, “They took me under their wings and really helped me adjust to the new environment. . . . I was a pretty young and inexperienced at 17. I really appreciated their friendship.” [2]

Green went on to earn his master’s degree (North Dakota State University) and doctorate (University of Louisville) in the field of inorganic chemistry and following a brief stint teaching at Kentucky State—Frankfort, a historically Black college, returned to Concordia in 1969 as a member of the chemistry department. Though a busy junior member of the faculty, still working on his doctorate, which he finished during his first semester of teaching at Concordia, Green unexpectedly became an informal advisor and counselor for the college’s growing body of minority students. There were roughly ten Black students on campus when Green arrived, but their number was increasing, reflecting the integration of higher education nationwide and the college’s new exchange program with Virginia Union University, an HBCU located in Richmond. The Greens discovered that students of color lacked a social center on campus outside of cramped space in a basement corner of Old Main, so they initially opened their residence across 8th Street as an informal gathering place. Dorothy Green was teaching at Moorhead State University, so Black students from MSUM gravitated to their home as well. One former student praised Green as playing a “magnificent role” in the growth and development of minority students on campus during these years. The administration soon asked Green and his spouse to help recruit African American students. He obliged. Thankfully, Green had completed his PhD in 1969. [3]

Richard Green’s recruitment efforts often took him across the country, requiring him to coordinate travel with vacation time and academic calendar breaks. He made trips with stops in cities like Denver and Dallas, oftentimes going down to Minneapolis and Chicago. Through his sedulous efforts, the number of students of color quickly rose to over sixty from a mere dozen the year prior. This in turn helped to increase and diversify the student population of Concordia. In 1971, Green proposed the formation of the Office of Intercultural Affairs (OIA) to provide stronger institutional standing for minority students. The administration agreed, appointing Green as the first director. OIA programming provided informal day-to-day support for an increasingly diverse student population; counseling for students struggling socially or academically; and established a Minority Student House from the existing Hudson House (821 6th St. South), a dedicated space for Black, Native, and International students. It also laid the groundwork for campus expression of Black politics and group solidarity, best expressed by the creation of a Black student union, Harambee Weuse (“we are together” in Swahili), in 1971. These were years of ferment and activism around the country for Black Power and Black Student Movements, culminating at Concordia with the Black Student Strike of 1976. [4]

Green left Concordia in 1972 to accept an administrative post as assistant to the president at Buffalo State University (New York), but when the Black student walkout occurred in 1976 he was a member of the Board of Regents. The college soon turned to him as a mediator. Green explained later that there were some very well-informed students who did not feel they were receiving the time and attention they deserved, and he was eager to help out. Green worked with the administration, faculty, and students to see what might be done immediately to help resolve matters, and what could be changed in the longer term to address the needs and concerns of students of color. Green observed, “I tried not to look at this as a quick fix, and to let the students know that somethings would not happen right away. From there [the students] were able to get some additional help. There was a sense of urgency, but it wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be. The situation did need attention.” The strike, Green observed, showed a need to do more than just bring African American students to campus. Their culture and backgrounds required understanding; their social and academic concerns needed a platform on which they could flourish. “[T]the students I taught and worked with grew immensely over short periods of time, coming into situations that were foreign to them. They existed in diverse communities, and this new setting [F-M] was not a very diverse community. I found when I came that [white] students had not met many African American students and they were curious about my background, my culture and my existence as a student of color. I’m not sure about the African American students that followed me.” A formative event in the college’s history, the student walkout represented a ripe learning moment for students and administrators alike when it occurred, and both parties seemed to grow through the experience. Sadly, Black student enrollments began an abrupt decline right at that time, such that building on lessons learned was short-circuited and momentum stalled. [5]

A dedicated scholar, Green’s departure to Buffalo also initiated his development as an able academic administrator. In the middle 1970s he accepted a position at the University of Massachusetts—Amherst as a chemistry professor and as Director of the university’s Southwest Residential College Division. Then hearing a return call to Lutheran higher education, Green served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Capital University (Columbus, Ohio) from 1976-1980, after which he assumed the role of Dean of Faculty and Vice President of Academic Affairs at Augsburg College, Minneapolis, a position he held for five years. A reflection of his versatile talents, Green then worked in private industry, at Honeywell, for over a decade. These were years, too, of civic voluntary engagement with Green serving as director for numerous philanthropic boards, among them, Minneapolis Society of the Arts, Fairview Deaconess Hospital, Minnesota Council on Foundations, and Minneapolis Foundations. He also served on the Board of Trustees of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. In 1993, Green took a hiatus from Honeywell in order to accept an appointment as interim president of Metropolitan State University (Minneapolis), the first of numerous presidencies at diverse institutions of higher education around the country, including Midland Lutheran College (Nebraska), Jefferson Community College (Kentucky), Lincoln University (Pennsylvania’s oldest HBCU), and United Lutheran Seminary following the merger of seminaries at Philadelphia and Gettysburg. Time and again, as happened during the Black student strike of 1976, Richard Green has been sought after to restore and repair, frequently entering the fray at difficult times of division, unrest, and institutional disharmony. Green’s success amidst great challenge is testimony to his preparation and wisdom and personal gifts of courage, steadfastness, and humility that have earned him the enduring respect and admiration of his peers in higher education. Concordia College recognized Green’s long career of service and achievement with an honorary doctorate of humanities in 2016. He was awarded the same honorary degree by the University of Louisville in 2002. [6]

Authors: Richard Chapman, Jacob Probst, and Graham Remple

Footnotes

[1] Dr. Richard Green, interview with Richard Chapman, 30 September 2017, Moorhead, MN, audio file and transcription (Jacob Probst & Graham Remple), Concordia College Archives (CCA); Richard Green Biographical File, CCA; Carroll Engelhardt, On Firm Foundation Grounded: The First Century of Concordia College (1891-1991) (Moorhead, Minnesota: Concordia College, 1991), 241.

[2] Green interview.

[3] Green interview; David Maggitt, interview with Richard Chapman, 21 July 2017, Golden Valley, MN, audio file and transcript (Rachel Johnson & Eric Watt), CCA.

[4] Green interview; Minority Student Directories and summaries, Student Affairs, Office of Intercultural Affairs (SA/IA), Subject Files, B10/F2 (Record Group 17.2.3), CCA; Richard Green, Carole Ann Hart, John Thigpen, & Cynthia Jenkins, “A Proposal to Relocate the Minority Student Cultural Center,” SA/IA, Subject Files, B10/F5.

[5] Paul Dovre, confidential President’s Newsletter for Board of Regents, 15 April 1976, and Dovre chapel homily, “The Reconciling Community,” 8 April 1976, Board of Regents (Record Group 2.3.1), CCA.

[6] United Theological Seminary profile, https://unitedlutheranseminary.edu/faculty-staff/richard-green/, accessed 21 August 2019; Richard Green Biographical File, CCA.